Your AI Is Faking Intelligence.

Last week, a friend sent me a screenshot and a single line:

"I think my AI just outsmarted my leadership team."

The screenshot was a wall of text from the new Gemini 3. The prompt was simple: "Given our cash runway, should we shut down Product B?"

The model answered with a structured analysis of unit economics, a sensitivity table on churn, a paragraph about "stakeholder trust," and a final, confident recommendation to kill the product.

It looked incredible. Concise. Nuanced. Even "empathetic."

Then he did something most people don’t do: he checked the numbers.

Half of them were fabricated. The rest were mashed together from last quarter’s memo and a blog post they’d once fed the model.

His conclusion: "If this came from a junior analyst, I’d be impressed. If I trusted it, I’d be bankrupt."

That’s the tension you’re living in right now. You are dealing with models that sound like senior operators, but are built on a mechanism that cannot think, reason, or "understand" in any robust sense.

I had a long discussion this week with my team about whether AI is actually "reasoning." Even among experts, the water is muddy. We see the impressive outputs and want to believe there is a mind behind them.

But if you want to build a true AI Operating System, you cannot afford that fantasy.

So I decided to write (an attempt to) a definitive argument for why LLMs—even the new ones—are not thinking. I want to give you a crisp, defensible way to explain to your board (friends, or yourself) why we don't hand strategy over to the machine.

This is my second letter on the subject.

This letter isn't easy to read. It requires your full focus. Grab a coffee, process this through your neurons, and let me know what you think by replying to this email.

Before we argue: pick strict definitions

If we don’t define words, this conversation turns into philosophy class.

If “intelligent” just means “maps inputs to useful outputs,” then:

- Your thermostat is intelligent

- Your dishwasher is intelligent

- A spreadsheet macro is intelligent

Or if "intelligent" meant "execute cognitive tasks that used to take a human (or a group of humans) forever to do," then your calculator is a Super AI.

For our purposes, let’s use deliberately boring, operational definitions – the kind a CTO or a safety team can work with:

Intelligence (for this letter)

The ability of a system to autonomously build, maintain and update internal models of the world and use them to achieve goals across novel situations.

Two key parts:

- It has models of the world (not just patterns in text)

- It can autonomously get curious and learn new things (dogs, cats, rats, have this ability)

- It uses them to act adaptively in new situations

Note: This definition covers only one form of intelligence—cognitive or problem-solving intelligence. Humans and animals also possess other forms: social, athletic (body movement), emotional, and more.

Yann LeCun (prominent AI scientist) offers a more restrictive definition that disqualifies LLMs and current systems outright: an intelligent system must have models of the world, persistent memory, and the ability to plan and execute.

While the first point is debatable, LLMs and current AI systems lack persistent memory and cannot plan and execute plans.

My definition is more permissive—designed to open the debate rather than close it.

Now let's define reasoning:

Reasoning (for this letter)

The ability to transform representations step-by-step according to rules, such that if the premises are true and the rules are followed, the conclusion must be true.

Two key parts:

- There are rules

- Validity matters more than popularity or style

Under these definitions, we can ask clear questions:

- Does an LLM build and maintain a world model it can update?

- When it “explains” something, is it following rules that guarantee valid conclusions?

- Can it autonomously get curious and learn new things?

The answer is obviously no for (c), but let’s discuss (a) and (b)

Hold those definitions in your head.

Now let’s look at what the model is actually doing.

The Coherence Trap (and the Parrot)

The trick your brain keeps falling for is something I call the "Coherence Trap."

LLMs are built on one core operation: Given a sequence of tokens, predict the next token.

That’s the whole contract. There is no goal of "truth." No goal of "consistency." No built-in notion of "valid argument." The training signal is brutally simple: "Did you continue this text the way a human usually would?"

Because human text is a TRACE of our thinking (and the best of our reasoning), the model learns to mimic the shape of our thinking. It learns that "Therefore" usually follows a premise. It learns that legal arguments sound a certain way.

We mistake Coherence (the flow of text) for Reasoning (the validity of logic).

The bigger the models become, the harder it is to see the distinction.

Cognitive scientists Mahowald and Ivanova gave us an interesting mental model for this: The Parrot That Passed the Bar.

Imagine a parrot that memorizes every legal case in history. On the Bar Exam, you ask: "In the case of X vs Y, which precedent applies?" It squawks back a flawless answer—because that pattern of words is in its repertoire.

Now put the parrot in a real courtroom and say: "Opposing counsel just made a novel argument that doesn’t match any past case. How do you respond?"

The parrot has no idea. It just flails through familiar legal phrases.

They used the concepts of Formal knowledge and Functional knowledge.

That is your LLM: Formally brilliant. Functionally unreliable.

But this was true in 2023. Recent models have actually bypassed these problems with one innovation that labs call "reasoning"—but which is actually: make the LLM talk more under the hood (you see a message saying "thinking") so the "patterns of reasoning" in text reveal more insights, and therefore the answer is far more accurate.

Some might say this is also what we do as humans—we talk more in our heads when we think deeper. Yes, but our sense of "reasoning" is far more sophisticated than just talking in our heads: we imagine scenes, move objects mentally, recall smells, memories, feelings, plans, read the state of the room, the emotional states of people around us, and compile everything together.

We have a far richer model of the world and that is shaped with our own, unique EXPERIENCE.

LLMs don't have any of that.

Three Structural Limits (That Scaling Can't Fix)

Most people try to "test" AI with riddles or math problems. Those are useless because models can just memorize the answers. If you want to know if a machine can reason, you have to look at the structural limits of its architecture.

Most people think LLMs reason—not because they're stupid.

Proving the difference between reasoning and "language coherence" is hard in a world where 99.99% of communication—and thinking—happens through language.

Modern image and video AI models also use language under the hood.

(In the physical world, the laws of physics make the AI flaws easier to see. The proof of non-intelligence of LLMs in the “world of animals” is straightforward too.)

But in our “language-based” world, it's much harder to spot.

There's a narrow window where you can spot the difference between “reasoning” and “fluency”.

Here are three tests that no amount of scaling has fixed—so far.

1. The Popular Lie (The Objective Mismatch)

Start with a thought experiment. Imagine a domain where 90% of the internet believes a misconception (e.g., a specific fallacy about economics or nutrition) and only 10% of the text contains the complex, mathematical truth.

What is the LLM’s job during training? Its job is to minimize prediction error. Its job is to predict what humans usually say.

The model that wins the training game is the one that gives the popular wrong answer with high probability and suppresses the unpopular right answer.

There is no internal pressure inside the machine that says, "Oh this is interesting! This is logically valid but unpopular, so I’ll learn more about it and say it anyway." The only pressure is, "This is what humans usually write."

A system trained to imitate human text is, by construction, a plausibility engine, not a truth engine.

For example, an LLM wouldn't produce the argument of this letter (with high probability)—because it's not the popular view on the internet.

2. The Twin Worlds (Correlation vs. Causation)

Most decisions you make are causal: "If we switch to remote work, what happens to productivity?"

Here is the problem: From text alone, you often cannot identify the true causal structure. Imagine two parallel worlds regarding business strategy:

- World A: Companies that invest in R&D during downturns outperform because innovation creates competitive moats.

- World B: Companies that invest in R&D during downturns outperform simply because only wealthy companies can afford to invest (survivorship bias).

In both worlds, the Harvard Business Review articles and LinkedIn posts look identical: they celebrate "bold R&D investment."

Since the LLM only sees the text, it has to collapse those "Twin Worlds" into one representation: "Here is how humans usually talk about R&D."

It learns the narrative, not the mechanism. It can write a perfect strategic memo that accidentally optimizes for the wrong causal model because it doesn't know which world you live in.

Medical Domain Example:

World A: Taking Vitamin D supplements prevents depression because it directly affects serotonin production.

World B: Taking Vitamin D supplements correlates with less depression only because people who take supplements also exercise more, sleep better, and have higher incomes.

In both worlds, the internet is full of testimonials saying "I started taking Vitamin D and my mood improved!" The text distribution is identical, but the causal structure is completely different. An LLM cannot tell you which world you're in—it can only tell you how people talk about Vitamin D and depression.

Business Strategy Example:

World A: Companies that invest heavily in R&D during downturns outperform because innovation creates competitive moats.

World B: Companies that invest heavily in R&D during downturns outperform because only well-capitalized companies with strong fundamentals can afford to invest during downturns (survivorship bias).

Both worlds produce the same Harvard Business Review articles and LinkedIn posts celebrating "bold R&D investment." The LLM learns the narrative, not the mechanism.

This is why an LLM can write a perfect-sounding strategic memo that accidentally optimizes for the wrong causal model. It doesn't know if you're in World A or World B—it just knows how executives in both worlds tend to write memos.

3. The Tool Dependency

This is the most pragmatic proof. Watch what the AI labs are actually doing.

Where do LLMs suddenly become reliable?

- Math: When you plug them into a calculator.

- Coding: When you run the code and force feedback.

- Planning: When you wrap them in search algorithms.

All the serious "reasoning models" in 2025 share the same pattern: An LLM in the middle, wrapped with tools that actually check, compute, or search—I’m going to say the magic word “an Agent”.

If the base LLM were already a robust reasoning engine, we wouldn't need the wrappers.

So people wrap the LLM with human-written code to generate something called an "agent"—which is more useful, but also more constrained by the human code wrapper.

The fact that we do proves that parts of the "functional knowledge" is being outsourced to the tools, not generated by the model.

The Brutal Benchmark: Skill vs. Intelligence

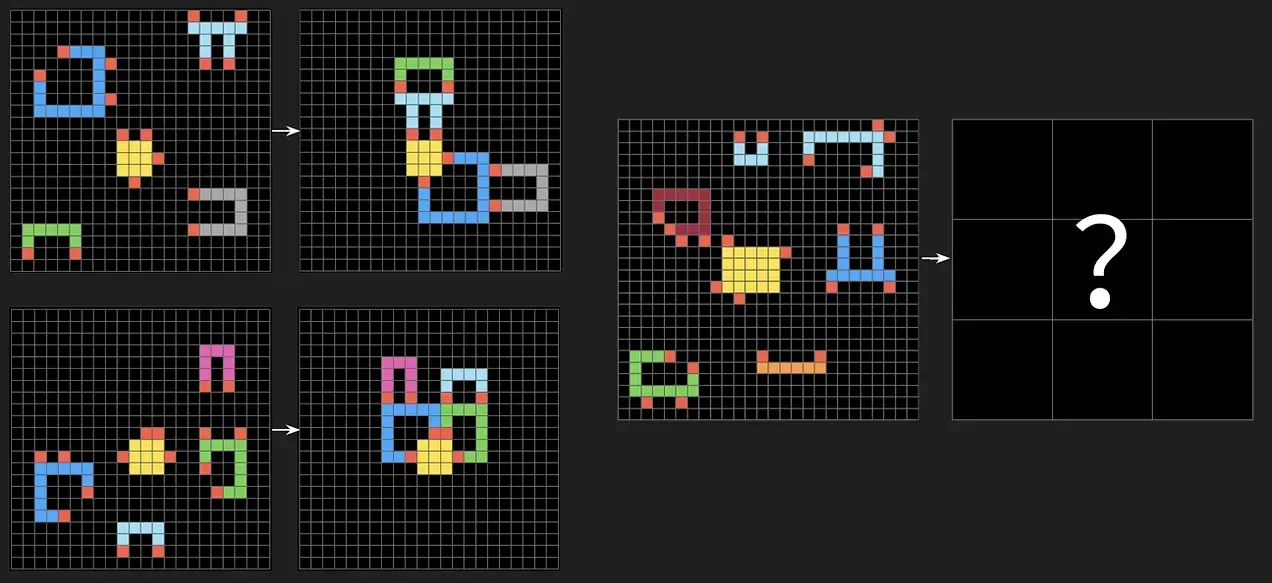

If you need one final proof, look at the ARC Benchmark by Google researcher François Chollet.

Most benchmarks test Skill (Have you seen this problem before?). ARC tests Intelligence (Can you infer a new rule on the spot?).

It gives the AI simple visual puzzles (colored grids) where the exact answer isn't in the training data. The results?

- Average Humans: ~98%

- Pure LLMs: ~20–40%

The takeaway is stark: LLMs are Crystallized Intelligence monsters (stored knowledge), but they have almost zero Fluid Intelligence (adaptive reasoning).

Some might say: So far.

Perhaps—but new models would just get better at talking about what they see... and talking... and talking... until a "consistent" answer would eventually come out.

Why not—but that's a very inefficient form of intelligence anyway.

The Wall of Novelty

This is where all of this hits your business.

LLMs live by Interpolation: Taking a new point inside the cloud of things they’ve seen before and filling in the gaps. If you ask for a polite email, they interpolate beautifully.

But the work that determines your company’s fate is Extrapolation.

"My CFO is secretly job-hunting, our VP Sales is feuding with Product, and we have 11 months of runway. Do we spin out Product B or kill it?"

That exact blend of politics, cash, people, and timing has never existed before. If you are off the edge of the training cloud. You’ve hit the Wall of Novelty.

That wall is harder to hit now—as LLMs grow larger, they've seen nearly every situation (or something similar) written on the internet, and they're better at mixing and combining those "seen" situations.

Humans (and animals) don't have all this knowledge, yet we're able to extrapolate using first-principle reasoning.

What does the model do there?

- It drags you back toward the average of vaguely similar situations.

- It replays generic narratives ("align incentives," "communicate transparently").

- It hallucinates specifics to keep the story smooth.

LLMs are Interpolation Engines. If you let them "extrapolate" for you, you get average answers. Your competitive advantage lives beyond that average.

The AI OS Principle

So, if they don't think, are they useless?

Absolutely not. They are the most powerful cognitive lever ever invented.

The power of LLMs lies in their vast knowledge—knowledge you'll never hold in your brain alone.

Combining that knowledge with your unique capabilities is a superpower.

But you need to use them correctly.

Here is the rule for your AI Operating System:

You own the Logic.

The model owns the Coherence.

You Own (Human / Tool Side):

- Facts: What is actually true in your system.

- Constraints: Budgets, ethics, risk tolerance.

- Strategy: What you are optimizing for.

- Causal Models: "If we do X, Y tends to happen."

The Model Owns (LLM Side):

- Drafting & Rewriting: Making it clear.

- Exploration: Offering 5 different viewpoints.

- Narrative: Turning your raw data into a story.

The Golden Rule: Never ask the model to determine what is true. Ask it to express your truth so humans can act on it.

The Takeaway

If someone asks you if AI is intelligent, here is your answer:

Under a strict definition—a system that have memory, curiosity, builds grounded models of the world and uses them to achieve goals across novel situations—No.

If someone asks you if AI is reasoning:

AI simulates and combines “reasoning sentences” so well with knowledge today that it's hard to PROVE they're not reasoning. But benchmarks like ARC prove they can't—so far.

They compress how humans talk about the world. That’s useful, but it’s not intelligence.

They optimize for plausible text, not true conclusions. They are interpolation monsters, not extrapolation engines.

"Reasoning models" are just better wrappers and better chatterboxes—not new minds.

Use it as a lever, not a brain. That’s how you build an AI Operating System you can actually trust—without lying to yourself about what’s on the other side of the prompt.

Until the next one.

— Charafeddine (CM)